Episode 10 Fact 1: Foundations of Maori Art

Māori had no traditional word for art because it was such an integral part of life. Form and function were intertwined in such a way as to serve both a practical and symbolic purpose. Fish hooks, for example, were carved to acknowledge the origin of carving from the realm of Tangaroa god of the sea and to please him resulting in a good catch. These precious hooks were then worn around the neck and therefore served another purpose as decoration.

A beautiful example of Māori Mātau design. At the top is a stylised head which has a practical function in securing the line but also illustrates the Māori belief that objects are individuals in their own right. Image Te Papa.

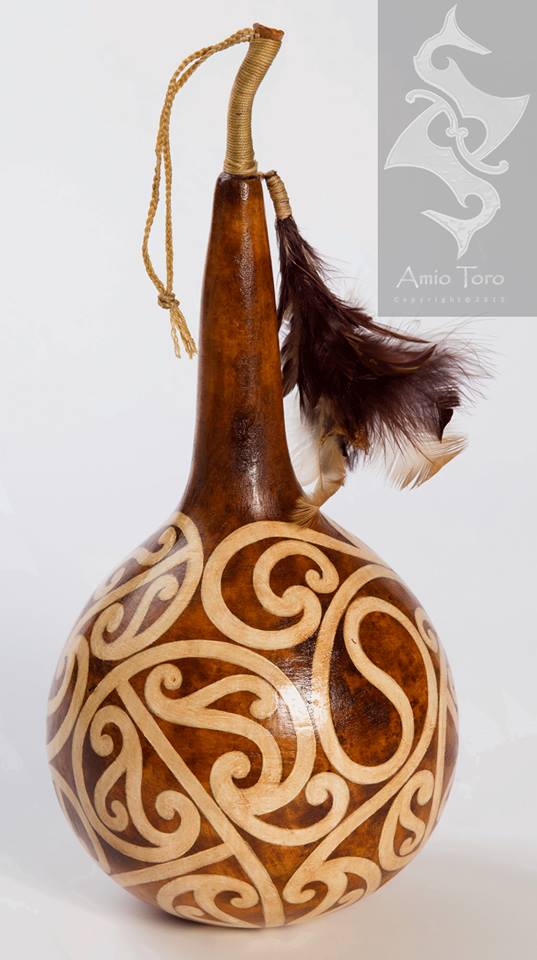

The idea of giving respect to material things both in their original form as plant, wood, stone or bone through to crafted, decorated items permeates Māori society because in the Māori worldview, everything is personified and has 'whakapapa' or genealogy which can be traced back to the Gods. An item such as the Poi, for example, has its own whakapapa. Poi are the children of Raupō (Bulrush) and Harakeke (Flax) and they in turn are the offspring of Tāne Māhuta the Atua of the Forest, and Pakoki and Repo the Swamp Maiden. Tāne Māhuta is the son of Papatūānuku the earth mother and Ranginui the sky father. It follows then, that all creation is half physical and half spiritual.

The story of creation of the poi, as told in this contemporary performance by Kahurangi Maxwell, Tiria Waitai and Talei Morrison. www.poi360.nz.

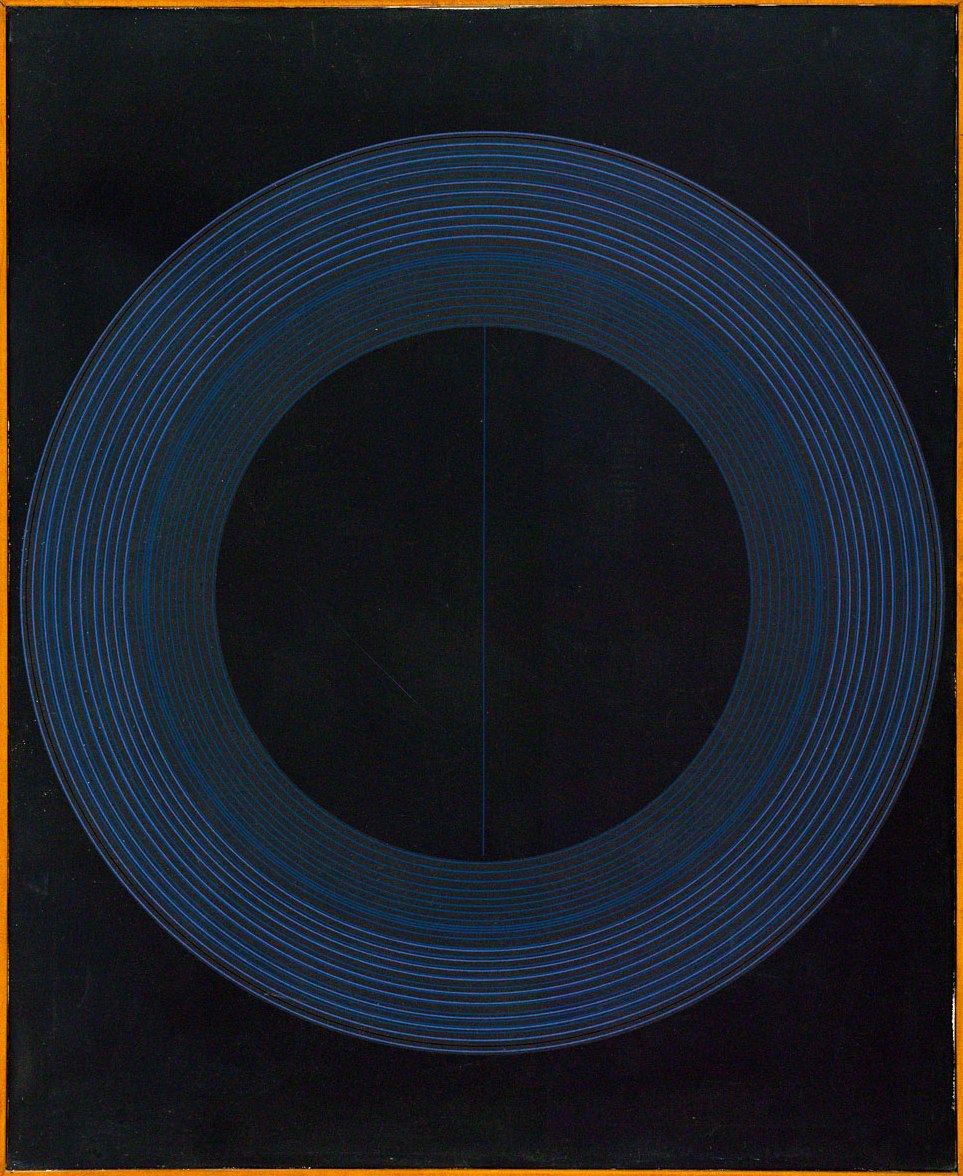

Māori art makes frequent reference to the balance between spiritual (ira atua) and physical (ira tangata) Whether the art form be the curving Kōwhaiwhai patterns that adorn the roof panels of a meeting house, or the geometric Tāniko patterns edging beautifully woven feather cloaks, there is a concern to express the idea of duality using a contrast of dark and light, negative and positive space, patterned and un-patterned surface. In many carvings for example, the cut out part of the shape contributes to the design as much as the object itself.

Waharoa by Katz Maihi and Boydie Te Nahu for Ngāti Whātua o Orakei. Image Toitū Design

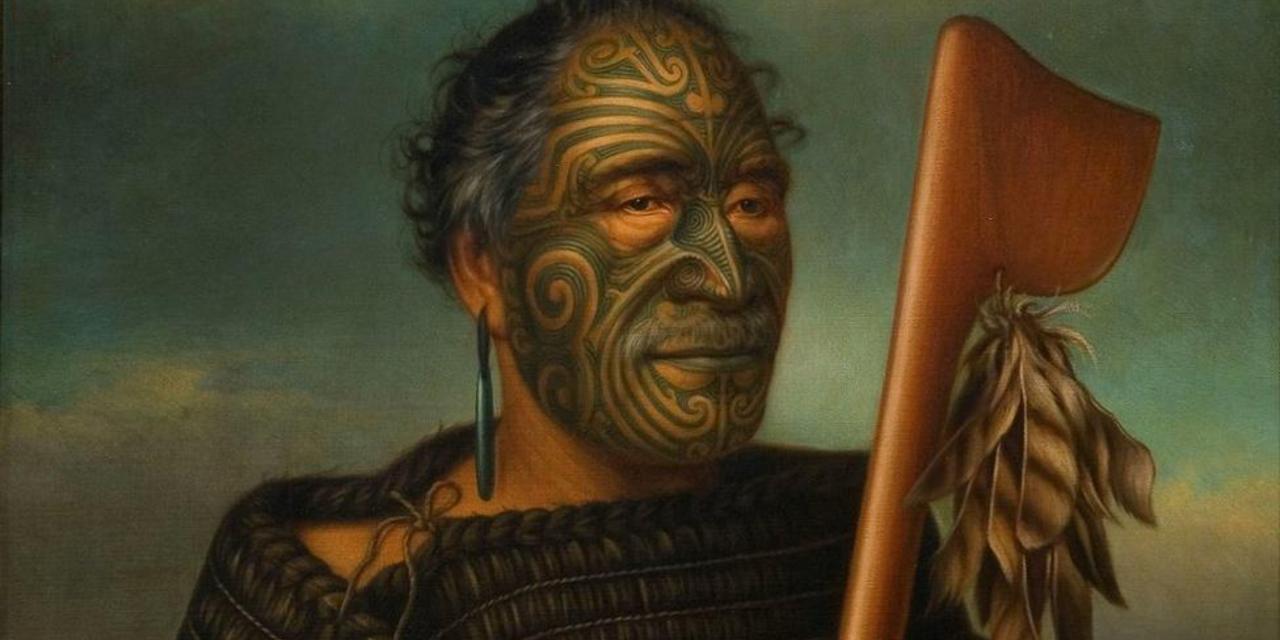

Traditional Māori art is primarily conceptual, so that conveying an idea is more important than visual accuracy, though if the story is known a likeness can usually be perceived. The koru, a stylised representation of a new fern frond unfurling, is one of the most common elements in Māori art and symbolises the many positive concepts in life that parallel the vigour with which the fern frond unrolls and grows into maturity. Its use also reminds us that its life force is dependent on the parent fronds that support it. In an oral culture, abstract shapes such as these were an efficient way to depict complex stories.

The effects of European colonisation caused a significant change in the role of art and the art maker in Māori society. After continuous attempts at suppression of Māori identity and culture, the 1960s and 70s saw a cultural renaissance develop alongside a growing political voice. Contemporary Māori Art began to be used as a method of protest and as an assertion of Māori identity and beliefs. Many young artists responded to their Māori heritage, urban situation and Western education by producing works that were a melding of traditional and non-traditional mediums, and utilised methods both Māori and European. The term ‘Toi’ or ‘Mahi Toi’ now encompasses Māori art in all its various forms both old and new.

Ref: Contemporary Māori Art - nzhistory.govt.nz, Kura Koiwi Bone Treasures - Brian Flintoff.